The Friction and Flow between Form and Function. Musings on Jupiter and Mercury

In my "day job" (sigh), I work with educational technology. Training for this career required that I study learning theories, pedagogical models, and other abstract concepts related to education; but also, I needed to learn about the world of software programming and other technologies used in the field (I know JUST enough coding to be dangerous!) Every day, my work connects the abstract with the practical— I bridge between the lofty goals of "helping students learn" with the nitty-gritty realities of "this software does XYZ, here's how to set it up and use it." In other words, my career is one that spans the domains of Jupiter and Mercury. It is a polarity I think about a lot.

Jupiter and Mercury form what some call an "axis of knowledge," with Jupiter ruling the higher domains of abstraction, philosophy, meaning, and purpose; and Mercury ruling the domains of technicalities, rudiments, definitions, applications, and specifics.

- Jupiter is the forest; Mercury is the trees.

- Jupiter is the goal; Mercury is the steps to get there.

- Jupiter is the story; Mercury is the letters and words.

This polarity, like all polarities, is built of two extremes that work paradoxically, both in tension and cooperation with each other. Each polarity needs the other, even as they oppose each other. Together they form our ability to "know."

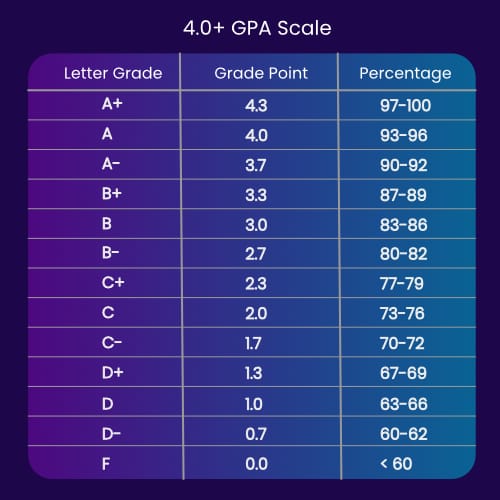

Here is one example of this polarity in the world of education. We are all probably familiar with the system of "grading" or "marking" student's work, to inform them how well they performed on an educational task (such as writing an essay, for example.). This system attempts to measure how well a student completed the task— with "100%" representing a complete understanding of the learning materials, and lower numbers indicating deficiencies in understanding. The numerical values are converted into letters --usually A, B, C, D, and F– which give a very rough overview of how well the student understood the material. This grading system tries to convey something abstract (a student's knowledge) into symbols (the grades/marks), which indicate or display to the rest of the world how well a student is doing in their education. This display (the set of grades earned) is used like currency, allowing a student to advance from one class or school to the next, or from school into a career.

The problem is, we cannot actually measure understanding. "Understanding" occurs in a person's mind, and only the person herself can experience that directly. Any attempt to reveal that intangible information requires a system of symbols, which bring that information into a shared space, but these symbols are not the real thing. Symbols always convey reality only imperfectly. It is possible for a student to fully understand a lesson, but do poorly on the test. It happens all the time. Likewise, it is possible for a student to do well on an assignment, but in reality not understand the concepts at all. Our system of grading is quite flawed, I heartily admit, but in all my experience in education, I have not found a better one that works at scale. There are several alternate grading systems that exist out there, but they are difficult-to-impossible to implement, and none of them scale. ("Scale" means "able to be used and shared by a large number of people." For example, our current system allows a student to transfer from one university to another, with each institution understanding how well that student has performed in various subjects, via the transcript record that shows their grades in every class they have taken.) Whenever the Intangible travels into the world of the Tangible, there is ALWAYS a distortion that occurs.

Whenever the Intangible travels into the world of the Tangible, there is ALWAYS a distortion that occurs.

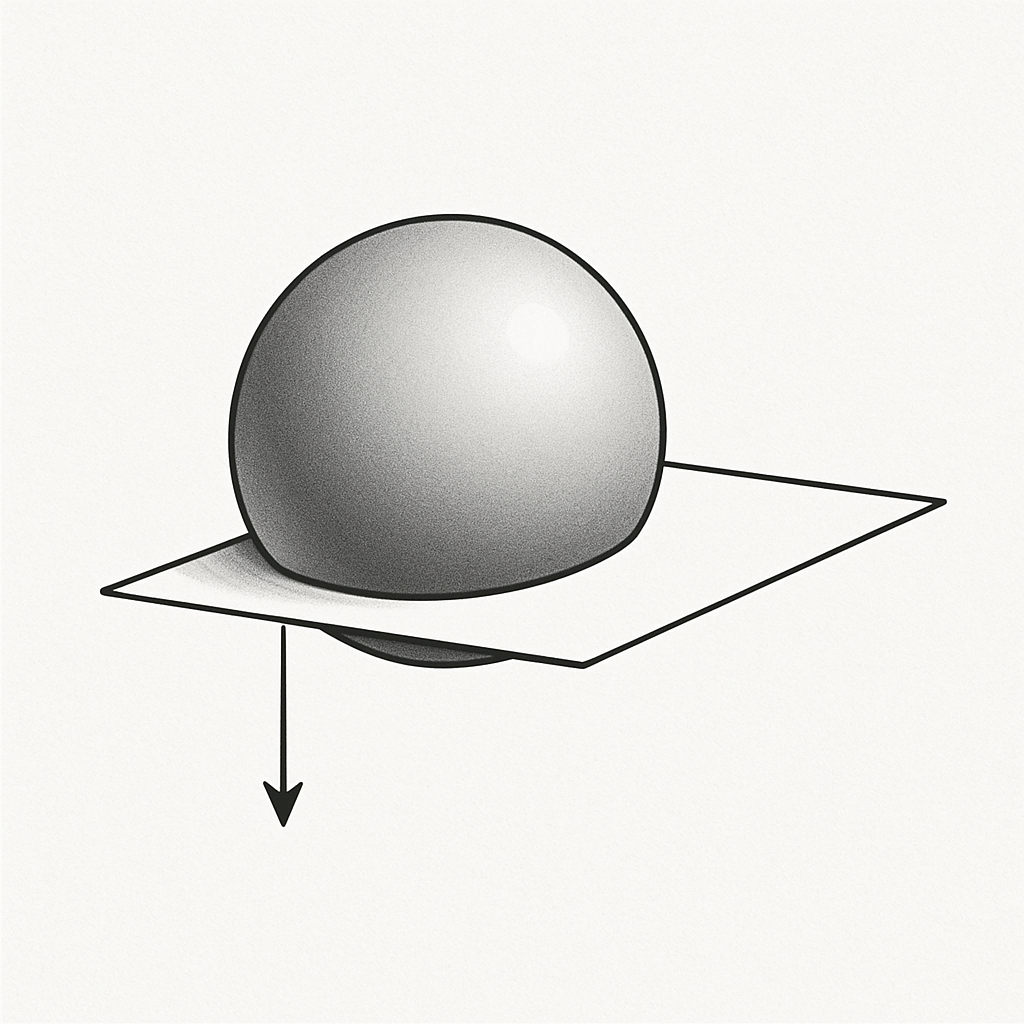

This problem of distortion can be demonstrated in the problem of moving from one dimension to another. For example, try to envision a 3-dimensional object (for example, a sphere) moving through a 2-dimensional space (a plane). It would start as a dot, then become a small circle. The circle would gradually increase in diameter until the sphere was half-way through. Then it would gradually decrease back to a dot, then disappear. If you lived in a 2-dimensional space, you would not be able to understand spheres; you would only understand circles. Your perception of a sphere would be distorted.

This dilemma is similar to the one Plato wrote about in his theory of the Forms. He wrote that our human level of understanding is like people viewing shadows on the wall of a cave. We can never actually view reality as it is; we can only view the shadows of reality.

The Cave is a helpful metaphor, one which has resonated throughout the centuries. But lately I have been questioning whether this framing is a good one, at least as far as trying to understand the Jupiter-Mercury relationship. The polarity between abstract and application is often represented in the framing I just provided above, with abstract realities presented as "higher," and applied or tangible realities presented as "lower." Abstractions are thought of (at least in spiritual communities) as more complete, more perfect, larger– just as the 3rd dimension is larger and more complete than the 2nd dimension. Abstractions are presented as the only parts that are "real," and the symbols and tools used are not, actually, "real." But I have often wondered if that distinction is unfair. The domain of Mercury is just as real as the domain of Jupiter. They are only different types of reality; one is not more or less real than the other.

As an example, let us think of how statistics are calculated. We never analyze ALL the data available; we only analyze the data that applies to the question we are wanting to answer. For example, medical researchers don't look at "everyone who dies of X disease," they look at "everyone who dies of X disease, between certain ages, without other confounding health conditions." Social researchers don't look at "Y factors in every country," they look at "Y factors in countries of certain population densities, not currently in a civil war." Etc. In order to draw meaning (Jupiter) from the data (Mercury), a LOT of the existing data must be ignored. This often presents its own inaccuracies and problems. How can we say that the narrative is "larger" than the dataset, when we are actually removing things from the dataset? Clearly, distortions also occur when the Tangible moves to the Intangible.

Distortions also occur when the Tangible moves to the Intangible.

Even though we sometimes use terms like "lesser" and "greater" when describing the planets, that phrasing shouldn't imply that their respective domains are actually less important, less complete, or less real than the other domains. It simply means their orbit around the Sun takes less time than the other object it is being compared to. Skills in all the domains are equally important. For example, if you've ever watched a highly Jupiterian type of person try to plan an event that is heavy on detail, you immediately realize how important the organizational powers of Mercury are. (They will forget to put forks in the food line or they won't remember to put a time on the invitations!) And on the other hand, we've all seen Mercurial types try to tell a story, but they just end up getting lost in the endless string of details and tangents, never getting to the point.

Knowledge requires BOTH rudiments AND schema; details AND concepts; function AND form. They are all equally important and valid. Both Mercury and Jupiter are required, for the advancement of human understanding.